On the 25th of June 2017, the Old-Catholic Church in Amsterdam hosted a symposium on the question whether there is such a thing as a specific priestly spirituality. For me, the clearest answer came from Revd. Mattijs Ploeger, lecturer in Systematic Theology. Defining spirituality as living close to Christ and His mission, he came to the conclusion that there is only one kind of spirituality.  Most parishes consist of a number of concentric circles. On the outside, there are those who only have a fleeting interest in spirituality. Then there are those with some involvement. The involvement of most Christians is not intense. The next (inner) circle has more similarities with the priest or minister. Here we find people who are interested in (studying) theology and perhaps even being ordained. The spirituality of the priest or minister is an intensified version of the general Christian spirituality.

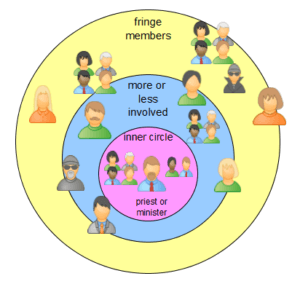

Most parishes consist of a number of concentric circles. On the outside, there are those who only have a fleeting interest in spirituality. Then there are those with some involvement. The involvement of most Christians is not intense. The next (inner) circle has more similarities with the priest or minister. Here we find people who are interested in (studying) theology and perhaps even being ordained. The spirituality of the priest or minister is an intensified version of the general Christian spirituality.

Central in his thinking is the importance of Baptism and the Eucharist, in which all who take part are celebrating and united with Christ. This connection is just as real as the connection between the priest and Christ. These two sacraments are not surpassed by any other sacrament, such as ordination. So how is it that we often think that priests have a unique spirituality? Mattijs gave several reasons.

- Clericalism, which is the idea that a church office means a higher rank or that ordination grants a person certain powers or abilities which others do not have. This does not mean there is no place for offices. Without recognised offices, by denying the importance of leadership and certain roles, these roles will often arise spontaneously, but then they will be much harder to control.

- Insufficient appreciation of the people of God as a whole and their connection with Christ. There may be a feeling that something needs to be transferred to an essentially godless group. What is needed is a more positive view of the Church (ecclesiology).

- Members may not appreciate their own spirituality and project too many things on the priest or minister. He or she is the one who knows. This is a sociological and psychological problem, exacerbated by the priest’s education and stipend. His or her expertise remains needed, but members should have their own prayer life, bible study and apply Christianity in their own situation.

Placing oneself only[1] opposite the laity does not work. Neither does constant questioning of one’s office. Finally, it should be noted that spirituality, even for a priest, is still very personal. When someone says, “I believe in my own way”, that is nothing special, but it could be the starting point for an interesting exchange of views.

Other contributions

Marleen Blootens, an ordained minister in the Dutch Protestant Church (PKN), described her personal vocation. She called her ordination a spiritual experience in itself. It was as if she received more space. It made me think that some of the intensity of the spirituality which Mattijs mentioned, might be due to the ordination itself and the time one is then able to spend on spiritual matters.

By way of an opposite, Rebekka Willekes, Mother Superior at a Roman Catholic convent, reminded us that John Cassian once said (in the 5th Century), “a monk ought by all means to flee from women and bishops”[2]. This reflects the patristic tradition in East and West of the reluctance of holy men to be ordained. Cassian all but equated the lust of the flesh with the lust for power. Rebekka’s fear, if anything, was therefore that accepting the office of Mother Superior, would leave her with less of a spiritual life. Fortunately her dedication to prayer, obedience and silence could be maintained in slightly different forms. For instance, silence can be practised in listening to others. We can often learn from each other instead of finding flaws. It is a privilege to see God at work in the other person.

Jos Moons, a Jesuit priest and professor, had also been speaking about recognising and greeting Christ in the other person. This is a spirituality of humility. It supplements and transforms the old title of the priest as “alter Christus” (another Christ). What I did not understand was why the title “alter Christus” is still maintained specifically in connection with priests once we are all encouraged to greet Christ in one another. I think this may or may not be connected to the Roman Catholic view that, during Mass, the priest is acting “in persona Christi”, i.e. representing Christ. Anyway, Pope Benedict XVI used and recommended the term “alter Christus” with specific reference to priests as late as June 2009, at the beginning of the Year of the Priest.[3] Also in the rest of the presentation, Jos Moons still appeared to work with two kinds of spirituality, a private one and one he shared with his students. He did, however, regard lay people as “fellow carriers of the Kingdom”, not as mere passive objects receiving grace.

Conclusion and comments

The difference between the spirituality of clergy (or others with a public ministry) and the people of God at large is one of gradation or intensity. There is, however, a danger of church officers actually becoming less spiritual as they receive more responsibility and power. Personality also plays a role, but that is always the case. This conclusion coincides with the one of the Faculty of Theology of the Tilburg University on its website.[4] There it speaks about the aftermath of Vatican II. Not only the difference as to spirituality came to be regarded as gradual, but even the differences with regard to the threefold office (ministerium) of Christ as a teacher, priest and king. It is just that ordained deacons, priests and bishops “have been put forward by the people of God to lead in services of the Word, to preside at the Eucharist, in teaching, community building, etc. For, we must never forget that in Jesus Christ, every baptised Christian has direct and unmediated access to God” (underlining my own). Therefore, the only qualitative difference between the general and the ministerial or hierarchical priesthood consists of meeting certain criteria [5] and receiving opportunities, as eventually expressed in ordination and/or commissioning.

Notes

[1] The word “only” is included because there are situations when a minister needs to oppose some view among the laity. This does not mean that the clergy is the opposite of the laity. Mattijs also proposed a change in my original diagram, so as not to give the minister his or her own “circle”. In his view the minister is “in one way or another” part of the “inner circle”.

[2] John Cassian, De Institutis Coenobiorum et de Octo Pincipalium Vitiorum Remediis, XI, 18 (in J.-C. Guy, ed., SC 108.444). The original text reads “. . . omnimodis monachum fugere debere mulieres et episcopos.”

[3] Benedict XVI, General Audience, Sain Peter’s Square, 24 June 2009, http://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2009/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20090624.html

[4] https://www.lucepedia.nl/dossieritem/wijding-sacrament-van-de/introductie-sacrament-van-de-wijding

[5] These criteria usually comprise a sense of vocation, a specific education and training, and certain personality traits.

This post is also available in: Dutch

[…] ← Previous […]

[…] [2] https://www.emendatio.nl/spirituality-one-two-types/ […]