The first three chapters of the book of Genesis seem an unlikely place to start our reflections about the priesthood, for priests and priesthood are not mentioned in them. However, sometimes things which are not spelt out are almost as important as the ones that are. The natural state of Adam and Eve before they sinned, was clearly one in which they were considered to have a direct communication channel with God. God not only spoke to them but is also described as “walking” in the garden of Eden just as the first humans did. Adam is said to have recognised the sound of God walking in the garden. It was apparently quite normal for God and the first humans to interact in ways that could be symbolised by a garden stroll. Under such circumstances, there was no need for a mediator or priest. This is an often overlooked aspect of the natural state of mankind.

Another way of expressing this initial and ideal state is by saying that both Adam and Eve were priests in their own right. After all, the way they had access to God resembles and even surpasses the way in which, later on, only priests and prophets would have access to God. Adam and Eve were standing before God. ‘One who stands before God’ is also the original meaning of the word ‘priest’. Adam and Eve did not even have to bring sacrifices in order to be acceptable to God. Perhaps that is why we haven’t usually recognised them as priests.

Also, we have long associated priests with beautiful garments. Two naked people somehow did not qualify. Especially not as that nakedness came to be associated with their sin, whereas in fact, their sin was more connected with wanting to be covered. Their nakedness should rather have been a symbol of purity and innocence. Another reason for not recognising the first humans as priests would be the prolonged patriarchal inability to regard Eve as a priest.[1] Adam, too, was classified more according to his sins than according to his state before he sinned.

The essence of the priesthood is usually summarised in two “vertical” aspects: the priest represents the people (or the whole of creation) before God as well as God before the people (or before the whole of creation). The first aspect has been rediscovered and re-emphasised since the Reformation. Cambridge New Testament scholar J.B. Lightfoot wrote, “The minister is … regarded as a priest, because he is the mouthpiece, the representative of the priestly race”.[2] The second aspect was the dominant view before the Reformation. It can still be found in the belief that a priest acts “in persona Christi” (in the person of Christ) during the Eucharist. According to Being a Priest Today, p. 30, the Church has voluntarily agreed that “it will concentrate its priestly prerogative to mediate the forgiveness of God on to one person”, the priest or ordained minister. For practical purposes, “whether their theology prepared them for it or not” priests are “often seen as walking sacraments through whom the presence of Christ can be touched. Like the hem of His cloak [they] are evidence that He is passing by”.[3]

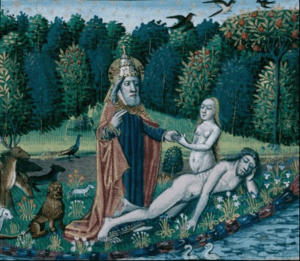

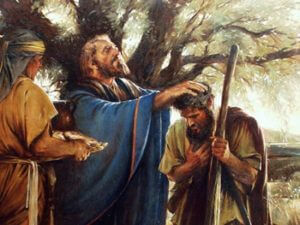

Now please have a look at this medieval picture of the garden of Eden. God, who is seen creating Eve from the side of Adam, is portrayed as a priest. It caused the person who catalogued this picture in Wikimedia to call the file “Adam, Eve, priest, animals and river”. In the Middle Ages, it was so common to think of male priests as the only possible representatives of God, that this is how God was visualised.

Now please have a look at this medieval picture of the garden of Eden. God, who is seen creating Eve from the side of Adam, is portrayed as a priest. It caused the person who catalogued this picture in Wikimedia to call the file “Adam, Eve, priest, animals and river”. In the Middle Ages, it was so common to think of male priests as the only possible representatives of God, that this is how God was visualised.

In reality, God cannot be pictured and Adam and Eve were the ones who represented God, having been created in God’s image, assigned to mediate the grace and the rule of God to the rest of the created world. I must confess that my first impression, too, was that the painting shows precisely one priest and two sick people receiving the sacrament, but it really represents the creation of Eve by God.

More familiar are the paintings in which we see Adam and Eve near a tree with an apple and a snake. Apparently, it was easier for artists and theologians to imagine and focus on the final episodes in Eden when our first parents were about to sin or had already done so. There was relatively little contemplation of Adam and Eve’s God-given splendour and functions before the fall. We also rarely see Adam or Eve in action, unless they sin or complain of their loneliness or nakedness or being deceived by others. This is a shame, for their creation in the image of God and calling to be channels of God’s love and truth must have made them glorious and splendid beings, certainly to begin with. Since a similar calling to reflect God’s goodness still applies to us, in spite of our sins and shortcomings, we would do well to study our original and ideal state as assumed in the two creation stories.

Further support for an implicit archetypal priesthood of Adam and Eve comes from chapter 2:15, where it says that “God took man and put him in the garden of Eden to work it and keep [preserve] it”. The Hebrew words used here are ‘abad and shamar. These are exactly the same words that were used for the ministry of the Levites and priests in Numbers 3:6-8 and for carrying out the rituals with regard to the tabernacle in Leviticus 8:35. Adam was presumably created outside Eden and then placed in the garden as if it were a temple where he should serve. Adam and Eve’s working and keeping Eden was a priestly function, namely to reflect and reveal the nature of God. Their care for the garden was an act of worship.

Too much intercession

When there is no need for (another) mediator or priest, it may well turn out to be a disadvantage to have another such agent interfering. This was clearly and for the first time illustrated by the role of the serpent. The serpent, as it were, stepped in between God and mankind, assuming the role of a spiritual director or middle-man. Not only that; he gave an incorrect interpretation of the divine will, exploiting a human weakness. The resulting confusion would probably not have arisen if Adam and Eve would have communicated directly with God, that is to say, if they would have taken their own role as representatives of God, created in God’s image, seriously. It is usually emphasised that the essence of their sin was wanting to be more like God. However, a problem of equal magnitude was that they reduced their own calling, responsibility and status as images of God and students, expositors and channels of God’s grace. They allowed their animal instincts and fears, symbolised by a snake, to jump to the conclusion that they were not getting the best possible deal.

There is nothing wrong with some doubt, but if we no longer allow the other (in this case the divine) party to answer any questions before deciding on our definitive actions, we are not using our best faculties. What Adam and Eve did was to temporarily avoid or skip their usual direct communication with the divine. They also suspended their own inner dialogue. I think the two are connected. Now their actions seem to have been determined by a strange combination of trust in an unreliable source, a need to gamble and a fear to miss out. That fear, although arising from within, was alien to the image of God, and was projected upon a third party. We still tend to blame others for our wrong decisions. Also, too often, we like to gamble, not always considering the possible consequences of new policies, products and in(ter)ventions.

Trust in such an “alien”, unpriestly and yet mysteriously priest-like voice, promising revelations and salvation from mediocracy, is where things went wrong. After that, mankind would repeatedly fall for this type of fear, whether arising from within or encouraged by actual third parties who would benefit if we turned to them for easy answers or grand schemes. Like nothing else, Genesis 3 illustrates how we often look for authority in the wrong place. Jesus himself spoke with great authority when He lived among us and yet he was met with scepticism and indignation. So what humanity seems to suffer from, is not so much a lack of trust, but misdirected trust. Perhaps what we call guilt is, in fact, a wrong kind of innocence.

Trust in such an “alien”, unpriestly and yet mysteriously priest-like voice, promising revelations and salvation from mediocracy, is where things went wrong. After that, mankind would repeatedly fall for this type of fear, whether arising from within or encouraged by actual third parties who would benefit if we turned to them for easy answers or grand schemes. Like nothing else, Genesis 3 illustrates how we often look for authority in the wrong place. Jesus himself spoke with great authority when He lived among us and yet he was met with scepticism and indignation. So what humanity seems to suffer from, is not so much a lack of trust, but misdirected trust. Perhaps what we call guilt is, in fact, a wrong kind of innocence.

The more serious “disobedience” is not related to any particular rules, but to disregard for the possible negative consequences of our actions and assumptions. Adam and Eve were mainly going for the short-term pleasure of the beauty and flavour of the fruit and the possible reward of wisdom. They rejected what they did not understand, in this case, “death”. Often we postpone thinking about the difficult issues while forgetting that the issues do not postpone their effect on us. We may also falsely assume that other, more eloquent or flattering or self-confident individuals have all the answers and will help us out.

Choosing life or death

There is definitely more going on in this story than Adam and Eve just being disobedient in the most literal sense. Salvation has to be wider than receiving forgiveness from an otherwise angry God for stepping over a seemingly arbitrary line. Could salvation be rather about the perception of who we are, about abundant life, discovering the effects of harmful assumptions and about truly reconnecting with God?

A hint in Genesis itself that “the fall” may not be about a particular disobedience as such, is found in Genesis chapter 1. In verse 29 God explicitly says, “See, I have given you every plant yielding seed that is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree with seed in its fruit; you shall have them for food.” In that light, the later prohibition may at first seem like a strange change of mind on the part of God. We may be inclined to regard it as one of the inconsistencies between the two creation stories, similar to the different order in which plants, animals and people are created. However, it is always good practice to look for a logical explanation, first.

The expression “every tree with seed in its fruit” virtually presupposes the existence of fruits without seed. So let us assume that the tree of the knowledge of good and evil had fruits without seed. Perhaps it was the only such tree. Anyway, now we can see that God did not first allow Adam and Eve to eat from all trees, only to forbid eating from one of them later on. God would have been consistent. The two creation stories would also be more consistent. Moreover, a fruit without seed is the perfect symbol of death, as the tree would not be able to procreate. This would have made it the perfect opposite of the tree of life.

The expression “every tree with seed in its fruit” virtually presupposes the existence of fruits without seed. So let us assume that the tree of the knowledge of good and evil had fruits without seed. Perhaps it was the only such tree. Anyway, now we can see that God did not first allow Adam and Eve to eat from all trees, only to forbid eating from one of them later on. God would have been consistent. The two creation stories would also be more consistent. Moreover, a fruit without seed is the perfect symbol of death, as the tree would not be able to procreate. This would have made it the perfect opposite of the tree of life.

Genesis and the archetype of the law

Did you notice that God gave Adam and Eve three commandments? In the first creation story, God tells them (a) to be fruitful and increase in number and (b) to rule over the earth and all its creatures. The latter is also called “the cultural mandate”. In the second story, God tells them (c) not to eat from the tree of death. In both stories, we find echoes of the commands in the other. Thus, the second story (in Gen. 3:16) speaks about childbearing, echoing (a). The first story, as we have seen, speaks of fruits with seeds, echoing (c). There are more such interesting parallels, but let us go back to the commandments themselves.

The second creation story is more anthropocentric (man in the centre) because man’s creation is reported before the creation of the animals. The corresponding commandment is suddenly a negative one, a “don’t” instead of a “do”. It is also cast in more legal terms, as a prohibition with an accompanying punishment. This single commandment is not unlike most of the ten commandments. 8 out of 10 commandments tell us what not to do, instead of how to live our lives. It is about this system that St. Paul will later write, “For I was alive without the law once, but when the commandment came, sin revived, and I died” (Rom. 7:9). And also in Galatians 2:19, “Through the law I died to the law so that I might live for God”. Christ not just added a new dimension to the law by summarising it in a positive way but speaks of new commandments (John 13:34). Similarly, if anyone is “in Christ”, he is a new creation. “The old has passed away” (2 Corinthians 5:17). These are characteristic descriptions of “the new covenant”.

So what consequences does this have, in retrospect, for that single commandment in Genesis, which triggered the first sin? If it was part of a package to be replaced by a new law of the heart, based on faith, then perhaps the initial commandments, including the prohibition to eat from the tree, were at best provisional as well. They were imperfect, not only in that they were unable to prevent sin, but, cast in human language, even seem to have contained some misperceptions about the nature of God and man. Having been written after the fall, the author may not entirely have been able to avoid writing from an imperfect human perspective, representing God as jealous. Why, otherwise, would having more knowledge of good and evil be so bad? When we look at the results of nuclear explosions, we can understand how too much scientific knowledge can be bad for our health, but too much knowledge of good and evil simply makes no sense. If anything, we still seem to have a shortage!

So what consequences does this have, in retrospect, for that single commandment in Genesis, which triggered the first sin? If it was part of a package to be replaced by a new law of the heart, based on faith, then perhaps the initial commandments, including the prohibition to eat from the tree, were at best provisional as well. They were imperfect, not only in that they were unable to prevent sin, but, cast in human language, even seem to have contained some misperceptions about the nature of God and man. Having been written after the fall, the author may not entirely have been able to avoid writing from an imperfect human perspective, representing God as jealous. Why, otherwise, would having more knowledge of good and evil be so bad? When we look at the results of nuclear explosions, we can understand how too much scientific knowledge can be bad for our health, but too much knowledge of good and evil simply makes no sense. If anything, we still seem to have a shortage!

However, we should also take into account that often in the Bible, the word “knowledge” does not refer to factual knowledge, but to experience. What God may have been trying to prevent, was that Adam and Eve would experience evil. In that case, God would have failed. This would then contradict God’s omnipotence. So perhaps we should look for yet another explanation.

The illusion of distance

I don’t think God ever intended to limit our freedom. God wanted us to take responsibility. That is exactly what Adam and Eve did not do. Adam pointed to Eve and to God. Eve pointed to the snake. In so doing, they, as it were, handed in their resignation as priests. In a Jewish blog I am following, David Bibi wrote, “When Adam sinned, perhaps the tragedy wasn’t so much in the sin as it was in his failure to admit, to ask forgiveness and to see what he could do to make up for it. Instead of responding with sorrow and a confession, he throws the sin back at Hashem stating, ‘It was the wife you gave me.’”[4]

No longer acting as priests, they could not remain in the temple of Eden. It was not so much God kicking them out, as removing oneself from office. Firstly, God did not withdraw the cultural mandate, the assignment to work the earth and rule over it. God only said it would become more difficult! In that sense, they still represented and resembled God (cf. Psalm 8:5, NIV[5]). In fact, after they had sinned, God told Adam and Eve that they had become even more like Him! Being sinners would not prevent the later (Levitical) priests from exercising their office (cf. Hebrews 7:27).

Although Adam and Eve definitely lost a great deal, we may have incorrectly assumed that our first parents necessarily lost (or never had) their priesthood and that they did so forever, and for all generations to come.[6] Later, when select minorities were “priested”, these exceptions may have been regarded too hastily as confirming the general “rule” that the majority of us, ordinary mortals, could never be priests. Many a Jew or Christian, while their “professional” priesthood remained silent, would even conclude that they themselves had no calling whatsoever.

Secondly, it should be noted Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Eden did not follow immediately after their sin. It happened only after they hid from God. While still situated in Eden, the perceived distance between God and man had increased and God had to speak louder. At that time God was still freely available, but Adam and Eve were not. They thought they could not “face” God the way God showed His “face” to them. Shame is a strange thing. It may be related to guilt, but it does not have to. It is about how you think others will look at you. God was still looking at them in love, as we can see for instance by the fact that God covered their nakedness, something Adam and Eve were now worried about. However, Adam and Eve thought they could no longer be “close” to God. Whether this was caused by the disobedience, or whether the disobedience was caused by the perceived distance from God, does not really matter. There was a distance, which was not initiated by God, but by mankind.

We should even ask ourselves if this separation was something objective or whether it should rather be considered illusory. Mind you, an illusion is not something that does not exist. It is a misperception of reality which makes us behave as if the illusion is real. When we think that, by whatever mechanism, we are separated from God, while in fact, God is constantly looking for us, that may well be called an illusion. Objectively speaking, there may never have been an actual separation from God, but it would still seem true to us and determine our thinking and our actions.

We should even ask ourselves if this separation was something objective or whether it should rather be considered illusory. Mind you, an illusion is not something that does not exist. It is a misperception of reality which makes us behave as if the illusion is real. When we think that, by whatever mechanism, we are separated from God, while in fact, God is constantly looking for us, that may well be called an illusion. Objectively speaking, there may never have been an actual separation from God, but it would still seem true to us and determine our thinking and our actions.

Although the parable of the footsteps on the beach is not in the Bible, it does illustrate an important truth. When we think we have been abandoned, someone may invite us to look back and we may see two sets of footsteps in the sand. Sometimes we need another person to open our eyes to the reality of a divine presence in our lives. In this modern parable, even seeing just one set of footsteps is no proof of God’s absence. We would see the same thing if God had been carrying us.

Salvation through Christ

The above has consequences for the type of salvation which is needed. If God has never been absent, we don’t have a long way to travel to restore contact. That restoration will not primarily depend on lengthy rituals, large numbers of prayers or endlessly being taught by professional clergy. It will depend primarily on faith in Christ’s words that the kingdom of God has already come. In fact, it has never been absent. However, it became more clearly visible (revealed) through the incarnation and the outpouring of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. The law was only a “guardian [or: schoolmaster] until Christ came” (Gal. 3:24). The question is, do we need other schoolmasters after Christ dwelt on this earth and restored us to God’s family? The short answer is “no”. Christ is God’s definitive answer to the illusory and therefore paradoxically very real problems of this world.

The above has consequences for the type of salvation which is needed. If God has never been absent, we don’t have a long way to travel to restore contact. That restoration will not primarily depend on lengthy rituals, large numbers of prayers or endlessly being taught by professional clergy. It will depend primarily on faith in Christ’s words that the kingdom of God has already come. In fact, it has never been absent. However, it became more clearly visible (revealed) through the incarnation and the outpouring of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. The law was only a “guardian [or: schoolmaster] until Christ came” (Gal. 3:24). The question is, do we need other schoolmasters after Christ dwelt on this earth and restored us to God’s family? The short answer is “no”. Christ is God’s definitive answer to the illusory and therefore paradoxically very real problems of this world.

Having said this, the illusion of separation is still very strong. This has led to many new misinterpretations of what Christ accomplished for us and what He did not accomplish. Some assume that what we need is a long process of cooperation with Christ in order to be saved, in which our actions contribute as much as His sacrifice. Others are saying that we need only faith, but that faith cannot be real unless we act like a particular group of Christians do, or recite the same creed. Yet others claim that Christ only came to give us a good example and show some love and acceptance and wisdom. The problem with all these views is that there is a long way for us to go before we can truly reconnect with God. And the more we remain convinced that we have a long way to go, the more it will be true that we have a long way to go.

As long as this remains the condition for the majority of us, I think we need two things. First of all, we need to realise that Christ gave us permission to have direct contact with God. The great example of this, of course, is the Lord’s Prayer, which he gave to us and which starts with “Our Father”. You and I should seriously consider the possibility that God will answer such prayers! Secondly, as long as our original role as priests of the Most High still applies, but has not become “second nature”, we need teachers who will encourage us to develop it. I strongly believe that they should make an effort not to stand in between God and ourselves but by our side. Mediation would only create new illusions of separation.

Unfortunately, the illusion itself still makes us perceive a wide gap between where we are and where we should be or desire to be. If we don’t go for the hedonistic solution, we tend to fill in this gap with programs of self-improvement and rituals, by building a certain reputation or status, or by following lots of guides and dignitaries. Such human agents are only helpful in so far as they respect us, aiming for us to discover our own unique relationship to God, including our natural and equal contributions to the Church and to society. When it does not always work that way, it is perhaps because those teachers themselves are not continually aware of the way God is present with them and with all of us. Many are giving us what we (seem to) ask instead of what we need to discover about ourselves and our calling.

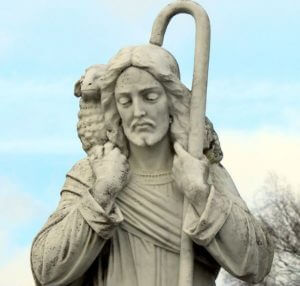

Christ as the new Adam

Another way of saying that we have divine permission to leave the illusion of separation from God behind is to call Christ the new Adam. This biblical title for Jesus expresses a fresh start for humanity. It was not so much a fresh start for God because God never left us. The incarnation can be seen as God’s ultimate reaching out. Although God was not far from us, God had to reach, as it were, through the illusion. When God came to live among us, it would be in the form of a sacrifice to end all sacrifices, also known as the Lamb of God. Anyone who feels that further sacrifices are needed to obtain God’s favour is either mistaken or ignoring what Christ himself revealed.

Another way of saying that we have divine permission to leave the illusion of separation from God behind is to call Christ the new Adam. This biblical title for Jesus expresses a fresh start for humanity. It was not so much a fresh start for God because God never left us. The incarnation can be seen as God’s ultimate reaching out. Although God was not far from us, God had to reach, as it were, through the illusion. When God came to live among us, it would be in the form of a sacrifice to end all sacrifices, also known as the Lamb of God. Anyone who feels that further sacrifices are needed to obtain God’s favour is either mistaken or ignoring what Christ himself revealed.

Christ set us free from a suffocating and stubborn prejudice, passed on from generation to generation, namely the idea that our sins are strong enough to push God away. In some Christian cults, this idea survives quite literally. Thus, after committing new sins or discovering that you followed unsound doctrines you are expected to be re-baptised. Mainstream churches are not without their own confusions, for instance about the sacraments. Are the sacraments progressively adding to one’s store of grace, gradually closing the gap between God and ourselves? Or are they more like seals of that grace and reminders of God’s unconditional love, helping us to be at peace with ourselves in spite of our failures? Have we become addicted to the repetition of words and gestures or are we genuinely empowered and given the confidence to resume our various tasks in this world?

Christ broke the vicious circle of always having to prove ourselves while expecting to fail because our ancestors failed as well. We no longer have to identify with either an endless sequence of failures or an endless sequence of presumption. Christ is the new beginning, enabling us to be sons and daughters of God once more, as well as fellow-heirs with Christ (Romans 8:17). It raises us from poor, helpless beings to what we were always meant to be (and inwardly remained), namely images and representatives of God. The book of Hebrews, which we will study more in depth later on, calls Christ our High Priest. This is another way of drawing our attention to what Adam and his children were meant to be and potentially remained, namely priests of the Most High.

Since Christ made a new start for the human race, it is never too late to rediscover and follow this our heavenly calling. This is not arrogance. It would be arrogant to claim “salvation” by forever remaining hearers while continuing to regard God as basically a distant schoolmaster. Just as God never left us, so our calling never left us. Just like nakedness, you can cover it and be ashamed of it, but you cannot shed it. Our need and calling to reflect something of the divine in our lives may get us into trouble, and sometimes make us feel a kind of inappropriate shame, as if we are robbing Christ of His glory, but a genuine calling cannot be denied or annihilated. It is not necessary to deny our calling and we are not robbing anyone’s glory. [7] On the contrary, not being in touch with that spiritual core of our being is the cause of much evil, and is not glorifying God. What mankind has done too often is to hide its best intuitions and take pride in the worst.

Realised eschatology and priesthood

The term “realised eschatology” is used by theologians to indicate a reality which was started by Christ, but is not yet completed until He comes again. In some ways, we are invited to live as if the Kingdom of God has already fully arrived while realising it hasn’t. Perhaps we should turn this around. As long as we treat the Kingdom of God as something purely belonging to the future, only pretending that some of it is available now, we are hindering its manifestation in the present. Could it be (without wanting to lean towards perfectionism) that the Kingdom is already here, in all its glory, but that we fail to see it and act accordingly?

Many Christians will be somewhat familiar with the New Testament expression “a royal priesthood” in 1 Peter 2:9. Most of them, however, will associate this with the future condition of God’s people, perhaps citing Revelation 1:6. Actually, neither of these two texts refer to the future. The first letter of Peter states, “you are a chosen people, a royal priesthood, a holy nation”. Revelation 1:6 is part of the introduction, not part of the visions of John. So when John the Revelator writes, “He has made us a Kingdom of priests for God his Father”, this refers to the time when Jesus shed His blood for us, as mentioned in the previous verse, and restored us. At the time of writing, the second coming of Christ was of course still in the future, as also testified by verse 7. So there is absolutely no reason not to be part of His chosen people and His priesthood right now unless we wish to limit the Kingdom of God.

Many Christians will be somewhat familiar with the New Testament expression “a royal priesthood” in 1 Peter 2:9. Most of them, however, will associate this with the future condition of God’s people, perhaps citing Revelation 1:6. Actually, neither of these two texts refer to the future. The first letter of Peter states, “you are a chosen people, a royal priesthood, a holy nation”. Revelation 1:6 is part of the introduction, not part of the visions of John. So when John the Revelator writes, “He has made us a Kingdom of priests for God his Father”, this refers to the time when Jesus shed His blood for us, as mentioned in the previous verse, and restored us. At the time of writing, the second coming of Christ was of course still in the future, as also testified by verse 7. So there is absolutely no reason not to be part of His chosen people and His priesthood right now unless we wish to limit the Kingdom of God.

The fact that we continue to disappoint ourselves and each other does not mean that we are not chosen. If we wait before we dare to look at ourselves as God’s royal priesthood, we are in fact saying that God’s grace depends on our worthiness, which is simply not the case. If we wait until Christ returns (whatever we imagine this to be like) we will have missed opportunities to be that which God now calls us to be. When we discourage each other from becoming more than disciples (pupils) who follow other disciples who followed yet other disciples, we are also frustrating God’s cause. Cf. Ephesians 4:13.

Paul regrets in 1 Corinthians 3 that he cannot yet address the believers in Corinth as people who live by the Spirit. One of the reasons is that one says, “I follow Paul” and another, “I follow Apollos”. This made them “mere humans” as opposed to people who live by the Spirit. He goes on, “What, after all, is Apollos? And what is Paul? Only servants, through whom you came to believe”. This text is often used to point to the harmfulness of divisions, but I think it is more than that. It also points to the harmfulness of not regarding church leaders as fellow-servants. We must learn to stand on our own two feet, not endlessly postponing to take the “solid food”. We must accept our place as flawed, but equal members of that “royal priesthood”.

Realised eschatology means that the healing of mankind has started and can no longer be stopped. It should definitely not be explained as if it is “unrealised eschatology”. It should not be made subject to human conditions and artificial phases of initiation. To those who don’t recognise a son or daughter of God, but presume to know the future, I would like to cite 1 John 3:2, which claims just the opposite, “Dear friends, now we are children of God, and it has not appeared as yet what we will be”. I must admit that I have long been accustomed to look to the future for fulfilment and wholeness. Now I am more and more discovering that God has already given us all we need, including acceptance of who we are in Christ. The kingdom of God is near (Mark 1:15) and we may once again serve God in the temple of creation.

Notes

[1] There are some who recognise Mary, the mother of Jesus, as a priest. She would have been totally justified if she had said (about Christ), “this is my body, given for you”. If this is so, then Eve would be able to say the same. The bias against women even led some authors to misread the biblical account. They assumed that Eve committed the first sin while “unsupervised” by her husband. In actual fact, Genesis 3:6 clearly states “she also gave some to her husband, who was with her”. Adam and Eve committed their sin together.

[2] Christopher Cocksworth and Rosalind Brow, Being a Priest Today, Canterbury Press, second edition, 2006/2007, p. 25

[3] Being a Priest Today, p. 32.

[4] Parashas Vayechi, Torah in Action / Shema Israel, 29-12-2017.

[5] Other translations have “a little lower than the angels”, but the Hebrew text clearly contains Elohim, which is God or gods.

[6] In this connection the following text from the deuterocanonical book Wisdom of Solomon 10:1,2 is also interesting: “Wisdom protected the father of the world, the first man that was ever formed, when he alone had been created. She saved him from his own sinful act and gave him the strength to master everything on earth.” Then Adam is described as righteous as opposed to Cain who murdered his brother.

[7] Compare Phil. 2:6, which also illustrates how answering a genuine call or identity is never theft, but a kind of humility.

Hello Jacob, I don’t suppose you would know where that statue of the Good Shepherd with sheep and staff is located?

Doing an image search makes finding where it is difficult as it has a free license for use, so many many people are using it! Hoping you know regardless!

Sorry, my search did not provide any new information, either. Let me know if someone else clears this up.