In religious contexts, the word “ministry” nearly always refers to the work of the clergy, i.e. of the paid professionals who lead our churches and have been ordained. They can go by the title of priest, chaplain, vicar, pastor, reverend or minister. In the Anglican church there are also so called Lay Ministers, but this is a relatively modern term, which still causes a lot of confusion outside and even inside the Anglican church. When someone is said to be “in the ministry”, this is almost always regarded as a reference to the ordained ministry. The two types of ministers are supposed to cooperate locally, but are often kept separate from each other at national, deanery or diocesan meetings when strategies are discussed. Somewhat like the UK with its House of Commons and House of Lords, so dioceses within the Church of England have their Houses of Laity and Houses of Clergy.

Terminology in the Netherlands

Before we go on to investigate the biblical origin and purpose of ministry, let me point out that the word is not used in my own language, at least not in a church setting. The closest word in Dutch would be “bediening”, but this is rather old-fashioned and hardly ever used. This is a pity, because it has a slightly wider scope than the ordained ministry. It could refer to any recognised gift or vocation in the Christian community. Instead, most Dutch churches speak of preachers and offices. In order to be called a “predikant” (preacher) or “dominee” one must be ordained. The offices include these preachers, as well as elders and deacons. In the Roman Catholic church a priest combines the concepts of “preacher”, “elder” and more. As everywhere, all Roman Catholic offices involve ordination.

Only a few expressions in Dutch still remind us of the Latin precursor of the English word “minister” (more on this in a moment). When “predikanten” have a meeting or work together they sometimes call themselves “the ministerium”. And since the Protestant church has a high regard for the proclamation of the word (similar to the status of the sacraments in the Catholic church), ministers like to point out, with a certain pride, that each of them is a “Verbi divini minister” (VDM). According to the magazine Zoeklicht (Searchlight) it is only ever used in obituaries for pastors, but there seems to be a small revival. I have many clergy and theologian friends on Twitter, and one lady theologian has this title as her nickname. Yes, there is also a website called www.verbidiviniminister.nl. It is devoted to sermons of the late pastor L. Kievit. An ordained Facebook friend of mine uses “verbi divini minister” to defend his opinion that no one should ever be allowed to become a pastor who has not studied Hebrew and Greek in depth.

The Latin word

So let us have a look where some of this pride and exclusivity could have come from, whether this narrow meaning of the word “minister” has become lodged in our language or the idea is just summoned occasionally, as part of other exalted names and titles, in order to signal to others that they can never quite be part of some exclusive group of religious experts. And how much exclusivity was originally intended?

The Latin word “minister” means servant or attendant and comes from “minus”, which means “less”. So instead of pointing to a higher status than someone else, the emphasis used to be on a lower status compared to someone. That someone could be a house owner, a noble or a governor. Being a minister was a secular job (compare our ministers in government). The majority of these servants were quite lowly. The church borrowed many customs and names from Roman society. Just like early church architecture and vestments were copied from the Romans, so the term “minister” was also adopted. After all, Latin was the language used in liturgy.

Two other factors were important. First of all, “minister” was the closest thing to the biblical Greek word “diakonos”. We will come to that in a minute. Secondly, once a bishop was no longer just another name for an elder (presbyteros or priest), but a regional supervisor, the priests and deacons came to be viewed as his servants, hence “ministers”. And because bishops were very important people, often with secular authority and large pieces of land as well, these servants were, on average, no longer so lowly and simple.

Influence of the Reformation

You would think that this would change as a result of the Reformation and its doctrine of the priesthood of all believers. However, in many places the abolition of celibacy gave rise to a new hereditary clergy. These families made sure that they remained powerful and influential. There are still many examples of pastors who themselves are sons of pastors and for whom this has been a clear advantage, not only because of their early familiarity with the meaning of “vocation” (more jargon to imply ordained ministry), but also because of good contacts and “a little help” along the way.

Partly subjective criteria for entering “the” ministry and a hard to verify process of what is called “discernment” assisted in keeping the clergy exclusive and traditional. A recent article in “Transforming Ministry” as well as my own experience confirm that people who just finished ordination training are more often than not hyper-focused on being accepted into that inner circle. Some will even share the pictures of their ordination every year.

I am not implying that there was no problem before the Reformation. Celibacy itself was also an instrument to keep the clergy exclusive. As these priests hardly had a life outside the church, relatively few of them were needed, they had a strong allegiance to the church, and they were admired for their devotion. In an article in the Latin American Post Sofia Carreño explains how financial considerations were another reason for the celibacy. Since celibate priests have no heirs, all their possessions and property usually went or returned to the church, which would only benefit the next generation of clergy.

More influence of the Reformation

In his book “The Stages of Faith”, developmental psychologist James W. Fowler gives an excellent description of the differences between faith and belief(s). Faith is strongly related to relationship and trust (Greek pisteo), while beliefs are of a more intellectual nature. While not denying that belief(s) played an important part when the Early Church defined its creeds, Fowler shows how the Reformation was even more about beliefs as propositions. As a reaction to certain practices and teachings of the Roman church, this was perhaps unavoidable. The Enlightenment further strengthened the emphasis on words and logic.

It can therefore hardly have been an accident that the aforementioned term “Verbi Divini Minister” was invented in 1562 by the Swiss Reformer Heinrich Bullinger while he was working on the so called Second Helvetic Confessions. Those confessions would lead to the Heidelberg Catechism, which was to become very influential in the Dutch and other Calvinist churches. Although Bullinger must have been aware that the Word of God is more than the Bible, namely Jesus Christ himself, the Logos, the term “Word of God” would still be taken quite literally. After all, Sola Scriptura (Scripture only) was one of the great motto’s of the Reformation, an antidote to the Roman claims that authority also existed outside the Bible, namely in the traditions of the church.

As I mentioned before, the words of the Bible, their study and proclamation (preaching) became for the Protestant churches what the sacraments are for the Roman church. When explaining “verbi divini” they emphasized that this word included the sacraments, but of course they did not recognize any sacraments that could not be clearly shown to have existed when the gospels were written. So, again, the vital role of the written word was demonstrated. Bullinger would add preaching to what was to be understood by “the word of God”. He is quoted as having said “Praedicatio Verbi Dei Est Verbum Dei” (the preaching of the word of God is the word of God). The assumption being that there was only one correct way of interpreting and preaching from Scripture.

Transcending differences

Using Hegel, we can see what happened. The criticism of Catholicism, however justified, had turned the original Protestant churches into bodies making statements. Beliefs had become dominant and would potentially threaten the role of faith as a relational phenomenon. I am certainly not saying that faith in God stopped, on the contrary, I believe it was initially restored, but the renewed faith leaned heavily on scholarship. As people could still come to different conclusions, many different protestant denominations were the result. This is a paradox, because the Reformers had assumed that Scripture was only capable of a single (better) interpretation. Some still assume this can be achieved if we study hard enough. But since then it has become clear (at least to myself) that opposing certain Catholic doctrines was not enough to restore faith as faith was intended.

Again I am risking gross over-simplification, but faith in the church and its offices was to some extent replaced by faith in probably more rational interpretations of Scripture. In fact neither of these types of faith could be comprehensive enough to provide ultimate meaning and direction. The very reliance on words would lead to many new kinds of authority which people would have to relate to, apart from the biblical words themselves. So what kind of ministry might be able to transcend these differences? What kind would neither rely on the authority of the church, nor on verbal inspiration or any other rigid system of bible interpretation? Here we need to go back to the Greek New Testament concept of ministry.

Ministry in the New Testament

The Latin word “ministry” was a translation of “diakonia”, which simply means service or support. According to A.T. Robinson (as quoted in a HELPS Word-study on Biblehub) the word means “one who kicks up dust (by literally running an errand)”. Vine, Unger and White (NT, 147) see a link with the verb dioko, which means ‘hasten after, pursue’ (perhaps originally said of a runner). In both cases there are elements of practicality and urgency.

In the New Testament diakonia was used for meal preparations (Luke 10:40), serving food (Acts 6:1), serving the good news (ministry of the word in Acts 6:4 and Paul’s ministry among the Gentiles in Acts 20:24,21:19), famine relief (Acts 11:29), and for the spiritual gift of serving (Romans 12:6-7). As you can see, this is a fairly wide spectrum including the care for physical and spiritual needs. In this sense, just about everyone is involved in some kind of ministry.

There is, however, a stubborn myth which says that there is an essential difference between the ministry of the clergy and the ministry (if they even call it that) of the rest of the church collectively. The first would be of a spiritual nature and the second would be either more tangible or in various ways supporting the spiritual ministry of the clergy. I believe several mistakes are being made here, all at once.

- The clergy and laity distinction. I have already written about this several times and will not repeat all that here. Let it suffice to say that this distinction is not found in the New Testament, that a professional clergy is of later origin and that it has all sorts of problems, some of which are admitted by the clergy themselves.

- The spiritual and material distinction. In Judaism, spirituality was always closely linked to the material world, to such an extent that the Old Testament seldom dwells on the afterlife. Prophetic promises always relate to an earthly future for the people of God, each person peacefully, i.e. without military oppression, sitting under his own vine and fig tree (Micah 4:4, 1 Kings 4:25, Zech. 3:10). We need to remember that when diakonos is gradually used in a technical sense, as one who cares for the poor in the Christian community, it is still only an example of service, with one type not being more or less spiritual than the other.

- In line with the previous point, it is wrong to suggest that “spiritual” service is a more sublime and specialized activity, and therefore restricted to certain specially trained officers. But don’t take my word for it. Would you agree that all Christians are Christ’s disciples (students)? I don’t know of any theologian who denies that we are all disciples. And would you agree that following Christ and learning from Him is a spiritual activity? Again, most Christians would say, yes. Then how about making other disciples? Certainly, that would be spiritual, too. Well, in Matthew 28:16-20 Jesus calls on all disciples to make more disciples! So Christians cannot only be said to be involved in some sort of ministry, but in spiritual ministry as well!The question which often arises is whether such mission or evangelism is only a corporate activity, or whether it is the task of each individual Christian. I believe this to be another false dichotomy. There is no reason why it could not be both. First, as we have seen, we are all disciples and therefore all in the ministry of making other disciples. Secondly, if for practical reasons we delegate some of this work to professionals, it does not mean we no longer have the corresponding responsibility.

- The idea of supporting the ministry. As we have seen, ministry is support or service. What are we supporting and whom are we serving? We are supporting and serving the world and each other and in so doing we serve the person and the message of Christ. How then did we come to believe that ministry itself is something we should all support? This can only be because we have come to see ministry as an activity of the few.A recent Anglican report actually defended the idea that we are to support our bishops in their mission to the world. This sounds logical when you assume that the only alternative is that bishops do it all by themselves. But it isn’t logical, because the assumption is incorrect. There is another alternative. How about bishops supporting all of us in our mission? Pope Gregory I (pope from 590 to 604) got it absolutely right when he called himself “servant of the servants of God”.

- Neutralization of the diaconate.

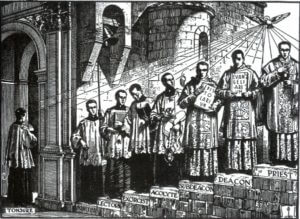

When the Roman church introduced 7 stages leading up to the priesthood, the diaconate was made into something temporary. As a result it also stopped (more than theoretically) connecting the spiritual and material dimensions of ministry. Perhaps that also explains the perceived need for “lay ministers” to take care of that connection. Even now that this 7 stage system is abolished, there are plenty of remnants. In all episcopal (threefold ministry) churches the diaconate is still usually a temporary phase leading up to the priesthood and considered as part of the spiritual or “real” ministry.

When the Roman church introduced 7 stages leading up to the priesthood, the diaconate was made into something temporary. As a result it also stopped (more than theoretically) connecting the spiritual and material dimensions of ministry. Perhaps that also explains the perceived need for “lay ministers” to take care of that connection. Even now that this 7 stage system is abolished, there are plenty of remnants. In all episcopal (threefold ministry) churches the diaconate is still usually a temporary phase leading up to the priesthood and considered as part of the spiritual or “real” ministry.

Note: Churches still like to divide ordination training into roughly 7 steps, vaguely reminiscent of the old minor and major orders, like the Archdiocese in Portland and the Community of St. Martin.A clever trick to deny that the diaconate has been made temporary, is to say that each priest is still a deacon. After all, he is still expected to render service. It sounds really humble, but there are several problems with this. It emphasizes that the priesthood is still a cumulative office, including just about all spiritual gifts and ministries and leaving little for the laity. It also doesn’t change the fact that material matters continue to be regarded as inferior. If the only real ministry is of a spiritual nature, which ministry is restricted to the clergy, and the diaconate remains locked up in that system, I think we have failed to heed the solemn warning in 1 Thessalonians 5:19, “Do not quench the Spirit”.How about deacons in Protestant churches? Although deacons have regained some of their original function and have not been encapsulated and neutralised within a system of full-time clergy, they are not regarded as ministers, either. On the occasion of 500 years Reformation an ordained minister I know boldly claimed that by 1517 AD the worldwide Catholic church had forgotten about her true mission. But I cannot support the implication that the Protestant churches always get it right. A “return to the sources of our faith” can also degenerate into a kind of idolatry, namely the worship of academic qualifications or even the Hebrew language. As president of “the New Bible School” Pr. Ad van Nieuwpoort approvingly quoted a rabbi who said that the Hebrew language is what makes the Bible a holy book.

Where things went wrong

Before Jesus had the Last Supper with his disciples, he washed their feet, adding “If I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also should wash one another’s feet. I have set you an example so that you should do as I have done for you” (John 13:14, 15 Berean Study Bible). Some churches take this very literally, and the pope has sometimes done this, but it should be clear that Jesus meant more than the actual ritual, which has lost much of its meaning in today’s world, anyway, as we no longer walk in sandals on unpaved roads. Jesus was clearly referring to all kinds of service, in other words to the ministry we have towards each other!

Peter’s initial refusal to receive this service, “You shall never wash my feet!”, is telling, but it may have become a model in many of our churches. In other words, ministry is what we do for our superiors. If they tell us to preach to the common people, that’s OK, but God forbid that we actually minister to them and require them to be ministers as well. If they want to minister, it should be to us. Peter, often regarded as the first bishop, could not imagine what Jesus was doing or asking. When Jesus explained it and gave them a direct command, the disciples could not avoid thinking about it, but afterwards the urgency seems to have waned.

And so we still have this misguided consensus that ministry is something that (preferably ordained) ministers do for Christ. There are things they do for the laity, because Christ seems to expect it, like pastoral work and teaching, sometimes even sharing that ministry, but never as a radical inversion of who is supposed to minister to whom. Deacons are still understood as servants of the bishop, or worse, servants of a priest, who in turn serves the bishop, who in turn serves the archbishop, etc.

In Protestant churches advisory bodies and councils increasingly behave as authorities and regulators. Even strategies and risk management are prescribed, sometimes understandable, but often overdone. In many circles “freedom of conscience” and “responsible autonomy” have become dirty words. And the most important task, supporting everyone in their own ministry, tends to be neglected or is not even recognized as a task for the professional ministry.

In the example I gave before, of pope Gregory I calling himself “servant of the servants of God”, unfortunately his motivation does not seem to have been real humility. Gregory was actually trying to put John IV, the 33rd bishop or Patriarch of Constantinople in his place for being the first to assume the title of Ecumenical Patriarch and summoning other bishops. John was also known for his charity to the poor. Surely a contest of who appeared to be the most humble ecclesiastical heavyweight was not in the spirit of Christ’s ministry to the disciples. It just shows that using certain words like “servant” or “minister” in no way guarantees a proper understanding of the concept of ministry.

Could it be that those who faithfully serve each other and the world without ever claiming the title of minister, are the real ministers? And that they are joined by part of the clergy, namely those who understand they are no better than their fellow-believers? Who pay more than lip-service to the priesthood of all believers? Who understand why Jesus called all his followers his friends? There can still be elders or overseers (cf. Titus 1:5-7, 1 Tim. 5:17, 1 Peter 5:1-2). However, when it is finally accepted that we are all ministers, I can perhaps omit the word “lay” in my curious new title of “lay minister”. Either that, or skip the whole title. Not because I am so humble (I am not), but because I can see how, as a church, we messed these things up.

Leave A Comment