The following article is a response to “Thinking about ordination?”, a blog from 2016 by Father Marcus (in 2019 removed from his own site). This blog, which started with a picture of a giant dog collar, was posted on at least three different websites and has crossed my path several times. Father Marcus describes the hardships of being a pastor and then encourages those considering ordination to go for it, anyway. For reference, I have included the entire blog in a separate box underneath. Many readers (often clergy themselves) were deeply touched. Some thought the clergy were complaining too much. Apparently the blog could be read in several entirely different ways. I will try to explain why this is and then present a completely remodeled version.

This is the blog we are discussing in this article:

Thinking about ordination? Think again.

Dear person who is feeling a call to pastor,

If you’re seriously considering becoming a pastor, think again.

Entering this ministry will be one of the hardest things you will ever do. You are signing up for the possibility of working incredibly long hours and will need to develop and maintain safe boundaries both for yourself and your community. If you’re lucky you’ll be paid. If you’re really lucky you’ll be paid enough to support yourself and your family (if you have one). You will have to manage unrealistic expectations from every direction, including within, and you will have to say “no” sometimes. You will encounter incredibly difficult personalities who will project onto you every grievance they have towards God. You will think about quitting once a month and at some point it might become a weekly consideration. You’ll encounter the shadow side of the Church – the place where sexism, classism, racism, homophobia, and general human brokenness lurk (to varying degrees depending on where you serve). You’ll be tempted towards snark over vulnerability and stubbornness over conversion. You will have your strength and patience tested far beyond anything you have faced. You will have the button of your deepest insecurity pressed over and over again. You’ll be made to feel insignificant by the shear size of it all. You will feel a deep sense of loneliness sometimes. You will have friends who will walk away from you… and it will hurt. You will disappoint people. You will disappoint yourself. You will feel constrained by the vows you take upon yourself. You will give your life to it and wonder if it makes any difference at all. You will encounter unspeakable pain and you will cry many tears.

If you’re considering ordination as a pastor, think again…

…and then, for the love of God, say “yes.”

We may see humanity, even ourselves, at our worst, but we also get to see God at God’s absolute best. Sure, there are great difficulties ahead and no amount of seminary or mentoring can prepare you for most of it, but you are also entering that beautiful journey with God where every difficult moment is accompanied by God’s grace. You will be entering a vocation where the very foundation of your calling is to rely on the strength of God to navigate difficult relationships, heart-breaking pastoral encounters, strained-budgets, general angst and anxiety, and your very own weary soul. Just when you have reached the end of your strength, God’s strength takes over. God’s strength is made perfect even in our weakness.

At the end of the day, God doesn’t call us because we are wonderful, or smart, or gifted, or worthy. Ordination as pastors and priests isn’t about us. It is about reflecting the image of Christ into our communities in ways that bear witness to the power and love of God in our midst. We are called to love everyone we encounter – those who love us, those who hate us, and those who are indifferent to our presence. All the while we point beyond ourselves to the God to whom all things journey.

The role of the priest and pastor is to model what every single Christian is called into – a life of total surrender. Like Peter, we will go places where never wanted to go. Like Paul, we will be changed in dramatic ways. Like Jesus himself, we will bear a cross that will cause us to stumble. This ministry is a cross that leaves its redeeming mark on our shoulders as we follow the pilgrim’s path to salvation and abundant life and God’s grace is sufficient even in our stumbling.

The ordained life is a beautiful life, one of great challenge and greater joy and we get to see both, up close and personal.

If you’re considering ordination as a pastor, think about it long and hard. Like the man who builds a tower or the king who leads an army, consider the cost.

And then say yes to God who calls you and promises to go with you even in the most unclear places.

Maybe you can’t do this. That’s okay. Because God can.

If we read the blog as “we face many difficulties, but they can all be overcome with the strength and joy that God gives us”, we almost have a standard, gospel-like, encouraging message. We will hardly recognise any “complaints”, even if the difficulties which are mentioned are serious. However, if you were told, “It is only through super-natural strength that we can bear what you, your kind and some of our own colleagues are throwing at us”, you would probably not regard that as a compliment. However, that, too, is a message that can justifiably be heard in this blog.

I suspect the problem arises from too much focus on ordination without placing it in a larger context. That may easily come across as a denial of similar challenges in other professions. This is amplified by the great emphasis which is placed, for instance, on “thinking of giving up once a month”. Without in any way underestimating the difficulties of the clergy, for instance the “unrealistic expectations from every direction”, of which I have seen many examples, what I missed was the crucial insight that every Christian faces particular challenges, one not necessarily easier than the other, if we can measure them at all.

In fact, I think you can never quite compare between those things you haven’t experienced for yourself. So the assumption that ordination is something unique, is correct, but the implicit assumptions that your patience will be tested less in other professions, that the button of your insecurity will be pressed less often, that you will be made to feel less insignificant, that other professions are less about reflecting the image of Christ into our communities, that they come with more realistic expectations, those are dangerous assumptions. And I am afraid these latter assumptions will also make the ordained minister less effective in his or her ministry. They will prevent the clergy from fully connecting with the secular world, thus bringing about a self-fulfilling prophecy of mutual misunderstandings. So my message to those in doubt about ordination is a rather different one:

Thinking about not being ordained? Think again.

Dear person who is not feeling a clear call to pastor,

If you aren’t seriously considering becoming a pastor, think again.

Avoiding this ministry will be one of the hardest things you will ever do. In many cases, you are signing up for the possibility of working endless hours, just like in the ordained ministry, but usually without a formal assurance (or any assurance) that you will contribute anything towards the welfare of others. You will need to develop and maintain safe boundaries for yourself, as in the ordained ministry. In most cases, the clergy will be too busy, understaffed or underpaid to look after you more than superficially, but they will call you “the church militant” and “the lay army” in the hope that you will evangelise the nation in your spare time and at zero costs. You will not be able to do much to safeguard the community you live in from similar inflated expectations or even from abuse. In many cases you will just have to stand by and watch things go wrong, because in spite of cautious democratic reforms in the Church, most important decisions are still taken high up in the hierarchy, based on the assumption that the Holy Spirit works through them more clearly than through the “laity” and that, if not, the same Holy Spirit will always enable them to “discern” what the Church as a whole is saying.

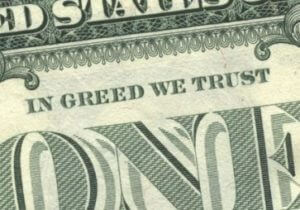

When not ordained, you will have the possibility of earning more, but that does not take into account rising income inequality in the general population. It means you could also earn considerably less. According to church rules, chaplaincies have to provide housing on top of clergy stipend, so you cannot really compare their salaries with those of secular workers. Higher salaries will also come at a higher price. This is not only about long hours and stress levels. In most lines of business as well as in privatised public services and mainstream politics, you will be expected to sell your soul and follow the principles of global capitalism and the free market during the week. Then, on Sundays, you are allowed to ask forgiveness for those sins and follow a different ideology. If you are paid well, this may suddenly change due to illness, being aged over 35, business being outsourced, etc. Within the Church, you can usually find a place to continue your ministry. This probably no longer applies to sexual offenders and those who have kept sexual offences under the lid, but there is still quite some mutual support among the clergy in matters of employment. Outside the ministry this can probably only be found in secret societies like the Freemasons.

Just as in the ordained ministry, you will have to manage unrealistic expectations from every direction, including within, and you will have to say “no” “sometimes”. You will encounter the same incredibly difficult personalities who are giving the clergy such a tough time. You will meet them inside and outside church settings. If you are a Christian, that will be reason enough for them to “project onto you every grievance they have towards God”. For that, you don’t have to be a minister. You will still be seen as a representative of “their” Church who makes it harder for them to feel at home. However, you will also have to deal, on a daily basis, with those who are atheists and former believers. It is true that these people prefer to attack church officers and ministers, but that does not mean other Christians are exempted. And since you will have more secular friends and colleagues, you will probably have to defend your faith more often than the clergy, unless you choose to hide your identity as a Christian. To this extended group of “incredibly difficult personalities” you will not be able to quote scripture in order to appease them or make them behave in a more forgiving way. I am not saying this always works with “Christian” trouble makers, but it will definitely not work with those who do not recognise the authority of the Bible.

Thinking of quitting

Some have estimated that, on average, all pastors think about quitting once a month or more. Which does not mean, of course, that they actually quit. I suggest that the only reason why this frequency sounds remarkable, is that we don’t tend to expect it in that profession. Objectively speaking, it is less remarkable. First of all it depends on how serious the thoughts of quitting are. This is not clear. Secondly, as an un-ordained Christian, you are probably also dissatisfied with your job in the sense that you can imagine a better one. You may even have an additional reason to dislike your secular job, namely that you are not able to spend all your time in a clearly recognised way promoting the kingdom of God and serving your fellow-believers.

Just as the clergy, you will encounter the shadow side of the Church – the place where sexism, classism, racism, homophobia, and general human brokenness lurk (to varying degrees depending on where you worship). The fact that you may not encounter them on a daily basis will be of little comfort, because you will be reminded of them each time you worship or join activities on weekdays or have contact via the social media. You will have even less influence than the pastor to change the group dynamics. You will not be bound by the sort of commitment the pastor made, so you will continually be tempted to change over to a different church or abandon the whole optimistic enterprise of a spiritual hospital where people are supposed to be healed and transformed. Of course you will also encounter general human brokenness outside the church, not necessarily less serious than inside.

Different responses

Whereas pastors may become stubborn to compensate for their vulnerability, you will be tempted towards apathy and cynicism. Your patience will be tested to the same degree as theirs, but, as I said, you will feel comparatively powerless to bring about spiritual change on a wider scale. The buttons of your insecurity will continually be pressed, even by the very people who are meant to empower you, which will make you feel even more insignificant than they feel about themselves. When they are intimidated “by the sheer size of it all”, you will be intimidated “by the sheer size of it all” plus the apparent and openly admitted inability of your spiritual leaders to cope.

Of course you will feel a deep sense of loneliness sometimes, just as the clergy does, because we all do. The clergy feel lonely because they are a minority in the Church and everyone depends on them, or so they think. You will feel lonely because you are an apparently insignificant cog in an anonymous majority called “laity”. I am not sure if and why pastors would lose friends more frequently than others, but if it happens to you, it will still hurt, and it will happen. You may not be in a position where you can disappoint many, except your boss and your family, but when you are honest you will definitely disappoint yourself, maybe for the very reason that you are not in a position where you can disappoint many. What the clergy tend to forget is that it is a privilege to be able to disappoint many, because that means they are also able to help many.

Whereas the clergy report feeling constrained by the vows they have taken upon themselves, you will feel constrained by the lack of structure in your life. Whereas the clergy are at least able to ascribe their career to a calling by God, even if they sometimes contradict this by speaking of “taking vows upon themselves”, your choices will be regarded as totally your own and you will have nobody else to blame for them. In theory the Church recognises other vocations than the “priestly” one, but in practice these will largely be treated with indifference, if not condescension. So when you give your life to some career and then have doubts about the overall positive effect, you will not only find yourself questioning your contributions, but also your ideology, as well as the reliability of those who have guided you. The resulting crisis of faith will not be less than if you were a pastor, and it will not necessarily be more visible or bring you more pastoral care or understanding.

Plot twist

So, if you’re not considering ordination as a pastor, think again…

…and then, for the love of God, whether or not you pursue ordination, say “no” to this false dichotomy of ordained and lay vocations.

Whether you are ordained or not, as a baptised Christian you are already part of the priesthood of all believers. The great Reformer Martin Luther even wanted all Christians to be called priests, but this was never followed up or properly understood. We have ignored this important doctrine to our own detriment. It has affected what we continue to call “clergy” as well as “the laity”. Indeed, the very existence of these categories have “helped” to perpetuate the mutual misunderstandings and isolation, the pain and suffering on both sides, the subtle insinuations and the less subtle collisions, the fracturing of the body of Christ.

If you are persuaded to pursue ordination, don’t do it for the reasons they often suggest to you. They may promise you that, in spite of all the disappointments in others and in yourself, you will also see God at God’s best. Ask yourself whether God’s revelations can be controlled by performing a ritual or even by making yourself available for the ordained ministry. When they promise you “a beautiful journey with God where every difficult moment is accompanied by God’s grace”, ask yourself if your God would deny the same amount of grace to those who struggle in other ways. Then ask yourself if “relying on the strength of God” is primarily the foundation of a call to ministry, or if it should be the foundation of each and every calling. Ask yourself if God does not say to each believer, “When you have reached the end of your strength, My strength will take over. My strength is made perfect even in your weakness”.

Indeed, it cannot be that when God calls people it is because they are wonderful, or smart, or gifted, or worthy. When careers are purely about ourselves they will leave us empty. The lives of all true disciples of Christ should be “about reflecting the image of Christ into our communities”. However, to even suggest that these things are specific or more foundational for the ordained ministry is a kind of hijacking of Gods purposes with everyone. In the context of a comparison[1] between careers, it makes one vocation more important and divine at the expense of all others. Ordained ministers are not the only ones who “point beyond themselves to the God to whom all things journey”. In fact, the more humble our service, the more it will point to God.

Equality or inequality of role models

It is ingenious but dangerous to emphasize that God does not call people to the ordained ministry because they are wonderful, smart, gifted or worthy. It provides an easy excuse when they are not so wonderful, less than smart, insufficiently gifted and/or unworthy. And, again, when this leniency is specifically mentioned in the context of the ordained ministry, it may leave you wondering if something like worthiness is even considered possible outside that context. Perhaps, rather than discounting certain qualities as reasons for God to call us, we should simply state that God does not expect us to be perfect, but this will apply whether you pursue ordination or not.

Be extra careful when you are told that “the role of the priest and pastor is to model what every single Christian is called into – a life of total surrender”. Listen carefully. We are all called to a life of total surrender. The role of the priest is to model such a life. Are we called to a life of total surrender? In that case we are called to something which is impossible. We can surrender to God, but we can never totally surrender, or we would be without sin. “If we claim to be without sin, we deceive ourselves” (1 John 1:8). Theoretically it may be possible, if we are not capable of fully surrendering to God, to be called to fully surrender, but we will not succeed. This should make us realise that we depend on God’s grace. Now that is something we can fully rely on. Sometimes, however, we even fail to rely on grace. Fortunately that does not mean that God’s grace is not sent and received.

Now ask yourself what it might mean to model a life of total surrender and whether this is a unique calling associated with ordination. Personally, I know only of one model of total surrender, which is Jesus Christ. There are lesser models, but they would not be models of “total” surrender. The apostle Paul was single and thus able to devote more of his time to preaching, although not all of it, because he remained a tent maker (Acts 18:3). Concerning remaining single he wrote, “I wish that all of you were as I am. But each of you has your own gift from God. One has this gift, another has that.” On second thought, although we are not called because we are “gifted”, we are called because we have received gifts. That is the very purpose of spiritual gifts, that they should be used in God’s service! They were given for no other reason.

In any case, Paul testified to the fact that besides Christ himself there is not one single additional type of model, but a plurality of partial role models. Each Christian reflects Christ partially, according to his or her gift. Paul would like to be their model, but realised that all believers in Corinth (not only the “ministers”) already had their own calling and were functioning as role models in their own right. This did not mean that Paul had nothing to offer or that he had no apostolic authority, but he never claimed it was his role to be “the” model of total surrender. Why would you want to be ordained if that is the role you are expected to claim for yourself? Does it not remind us of the Pharisees, who, according to Jesus, “pile up heavy burdens on people’s shoulders and won’t lift a finger to help”?

That would seem to apply particularly when surrender is prescribed without specifying what it would actually look like in concrete terms. Ambiguous types of surrender could quietly come to be regarded as including total obedience to the decisions of superiors, even when those decisions would interfere with one’s conscience, thus leading to internal and external conflict. Additionally, we should be careful not to confuse surrender to God with the type of emotional, almost sexual, gratification which certain personality types temporarily experience when they join a cult or otherwise allow their uniqueness to be overruled. When that experience wears off, new thrills may be sought in getting others to submit. Especially in the light of recent abuse cases in the church, far greater care should be taken in the way ministry is portrayed and recruitment takes place. Should ministry not be about lifting people up (including yourself), rather than revolve primarily around submission?

Weaknesses as evidence of resembling Christ?

I suspect many of the usual ideas about ministry go back to the outdated idea that (only) those ordained to the priesthood, can act “in persona Christi”. Those interested in ordination will be told that “we” will bear a cross that will cause “us” to stumble. Although this could have been applied to all Christians, the context surreptitiously narrows it down to the ordained ministry. The next sentence will make this even more explicit. “This ministry is a cross that leaves its redeeming mark on our shoulders”. The words “this ministry” can only refer to the ordained ministry. Otherwise the message would be nonsensical, calling the act of bearing a cross a cross in itself. Compare also one of the first sentences: “Entering this ministry will be one of the hardest things you will ever do.” This clearly refers to “becoming a pastor” in the previous sentence.

What is most interesting, though, is that the ministry is called “a cross which leaves its redeeming mark on ‘our’ shoulders”. I know of only one cross that leaves a redeeming mark (on anyone), and that is the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ himself. Although we all have to carry a cross of some kind, there can be nothing redemptive about it, unless you believe that some of us take part in the sacrifice of Christ, not only during the Eucharist, but through their vows and their entire lives as ordained ministers. St. Paul, however, calls upon all Christians to offer their bodies as a living sacrifice by way of “proper worship” (Romans 12:1), not by way of redemption! Finally, ask yourself if the word “mark” is not a subtle reference to the controversial doctrine of the “indelible mark” that priests were believed to receive on ordination. Check whether your heart beats faster at the thought of belonging to a priestly order in which perceiving yourself as a different human species is still quite acceptable. Ask yourself if it is OK that even their stumbling (which is an ambiguous word which may or may not include failures) is used as evidence that they represent Christ more than ordinary Christians could do.

So, if you’re not entirely sure about ordination as a pastor, think about it long and hard. Like the rich man who doesn’t build a tower for himself or the king who doesn’t lead an army, consider the cost of remaining an outsider. And then stand by your decision never to join the clergy for the wrong reasons. Say yes to God who calls you anyway and promises to go with you even in the most unclear places, places not even the clergy know exist. Maybe you can’t do this. That’s okay. Because God can!

Notes

[1] Some might want to deny that the original blog is a comparison. However, it clearly says, “You will have your strength and patience tested far beyond anything you have faced.” That is a comparison.

Leave A Comment