How often should we celebrate the Eucharist? Why do Roman Catholics, most Anglicans, many Methodists, Lutherans and Presbyterians have a weekly Eucharist (Holy Communion) and most other churches a monthly, quarterly or even annual Holy Supper? The Anglican way to approach such questions is to turn to the Bible, to tradition and to reason.

The gospel of St. Luke (22:15-20) tells us that Jesus shared a Passover (Seder) meal with his friends before He was going to suffer, and that they should do “this” in memory of him. Because of this mention of Passover many Bible scholars have serious doubts whether Jesus ever meant to introduce an entirely new ritual. The longer phrase “do this as often as you do it in remembrance of me” does not occur in any of the gospels, but it appears in St. Paul’s version in 1 Corinthians 11:25,26.

Reason suggests that “this” can only refer to something that was already being done or known, or it would require further explanation. What Jesus seems to say is that whenever “this” (the eating and drinking on such a religious festival) was to be repeated, it should be done with Christ as our ultimate sacrifice in mind, instead of or in addition to earlier and more limited instances (types or shadows) of salvation. Most likely the Last Supper and associated events would have had such an impact on the apostles that ever since even ordinary meals would remind them of Christ’s sacrifice.

The book of Acts, chapter 2, has a description of the life of the early Christians after the ascension. In verse 42 four things are highlighted: “And they devoted themselves[1] to the apostles’ teaching and [to the] fellowship (koinonia), [and] to the breaking of bread and [to] the prayers “. Several things should be noted in this important verse and the ones that follow:

- The “breaking of the bread” does not clearly stand above the teaching of Christ, the fellowship and the prayers. It was the combination of these 4 things that apparently enabled the apostles to perform the powerful works and signs mentioned in the next verse.

- Although the “breaking of the bread” symbolized, among other things, the fellowship within the body of Christ (the church), it did not replace the actual fellowship. It may even be claimed that the existence of a worthy sacrament depends on gratitude and willingness to share what we have with one another.

- No specific frequency is prescribed or reported. What mattered was devotion.

- Verse 46 explains that the earliest Christians worshipped in the temple, but the “breaking of the bread” took place at home.

From annual to weekly

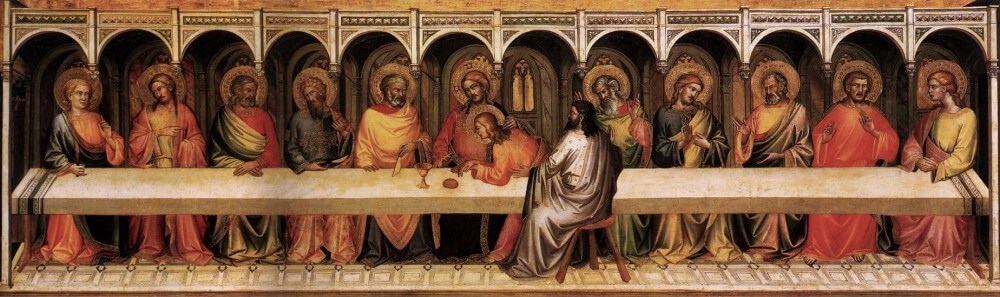

So how did the one-off example of Christ, linked to an annual feast, develop into a more or less regular custom among Christians of celebrating the Eucharist? The New Testament does not offer us too many clues. St. Paul makes it clear in 1 Cor. 11:20 that in his time the sacrament had not yet developed into a purely ritual meal. People were able to eat and drink too much, indicating an agape (love) feast. There is evidence from the writings of the church fathers, that these very excesses led to the decline of the real meals and the rise of a more stylized ritual meal. Changes in the cultural and religious context also played a part. The church would sever its bonds with the synagogue and be subject to Hellenization. The sacrament was no longer modelled after the Pascha, but came under the influence of cultic meals held during Greek mysteries.

Just as the resurrection came to be celebrated weekly on the day of the Sun, so did the new Eucharist. By the time the Church “went public” after the conversion of Constantine the Great in the fourth century, it was clear that the Eucharist was established as a central part of Christian life.

After the fourth century AD

After that, the Eucharist gradually became even more abstract. In medieval times most people would only watch from a distance as a priest pronounced some mysterious Latin prayers, consecrating and helping himself and perhaps a few assistants to wafer and wine. At the start of the Oxford movement, the Church of England regarded Morning Prayer as its main service. And they did not remember anything else. The Oxford movement then with some difficulty reintroduced the practice of earlier Christians (of post-New Testament times). Even the evangelical wing within the Anglican Communion inherited this weekly Eucharist, distinguishing them from other evangelicals and most protestant denominations. We believe that the Holy Spirit guided the church and that the practice of the early church should be taken seriously. We cannot, however, use this argument to prove that churches with a weekly Eucharist are right, and those with a monthly or quarterly Eucharist are wrong. Other reforms took place within our ecumenical partner churches, leading to slightly different results and theologies.

The meaning of the Eucharist

So it seems that our starting question cannot really be answered without paying more attention to the meaning of the Eucharist. In St. Luke and 1 Cor. 11 the most descriptive word, if anything, is “remembrance”. This is what Christ wanted us to do, to remember the meaning of His death. In Scripture and in Hebrew culture in general “remembrance” includes experience in the present, and relating the events and its lessons to oneself. St. Paul further explains the sacreament as a visual proclamation of the Lord’s death. Our way of celebrating will therefore have to keep Christ firmly in the centre and clarify His saving grace, with nothing being allowed to distract from it. Examples of distractions would be: a language that is not understood, complicated written or unwritten rules, the person or status of the minister, too much repetition so that the message is no longer heard, thoughts and fears of the communicant, and worshipping the externals of the Eucharist rather than Christ’s presence.

Some of these distractions no doubt originate in the mind of the communicant. But even then the local community has a responsibility to try and prevent this from happening. This is not necessarily easier than encouraging people to have regular communion. It would be a mistake to suppose that we have done all we can as long as we arrange plenty of opportunities to have Holy Communion.

With infrequent communion there is a danger of unfamiliarity or even fear. But with regular communion there is the danger of becoming over-familiar and going through the motions on the automatic pilot. Therefore a balance is necessary. People can become overly attached to a set pattern, usually hardly being aware of what is no longer being experienced. If the church would always merely have sought the approval of its members and provided exactly what they considered as most “normal”, there would never have been a restoration of the sacrament via the Oxford movement either.

A practice with intention

The conclusion is, as bishop Robert would say, that everything we do should be intentional. Things should not happen by accident, or because we have always done it that way, or because they are expected and comfortable. Receiving communion can be an intimate and powerful encounter with Christ, but only if we do not allow ourselves to become passive consumers, not even – or rather: especially not – when what we receive is pure grace. That is why the church will try to make sure that our way of doing things is both in line with a long and precious tradition and compensates for the current spiritual blind spots of churchgoers as well as our society.

[1] Other translations are: “were steadfast in”, “persevered in” or (KJV) “constantly attended to”.

Leave A Comment